Sir Cedric Morris

(1889 - 1982)

Surrealist Landscape

On the reverse, a keeper’s cottage, Wales

Oil on canvas

20 x 24 in – 50.8 x 61 cm

Frame size

26¾ x 30¾ in – 67.9 x 78.1 cm

Oil on canvas

20 x 24 in – 50.8 x 61 cm

Frame size

26¾ x 30¾ in – 67.9 x 78.1 cm

Tel.: +44 (0)20 7839 7693

Provenance

Gifted by the artist to Bettina Shaw-Lawrence;

Thence by descent within the family

‘In his flower painting Mr Cedric Morris has broken new ground. With his knowledgeable carelessness of production, he erects a screen of multi coloured petals. There is a frankness and simplicity about his treatment, as there is a natural instinct in his science, which has introduced an unwonted freedom into the conventions of this branch of paintings’, so wrote the esteemed art critic T.W. Earp in The Studio magazine in 1928. Cedric Morris remarked how he used to watch his mother work on her tapestries from top left to bottom right. His pictures have this element of structure within, and he often worked in that way.

Outlining his own thoughts about flower painting for The Studio in 1942, Cedric expressed admiration for Chinese flower painting, but also Van Gogh and the Surrealist Max Ernst. He never sought botanic accuracy preferring to convey realism and an inherent being within plants: ‘The artist must have been intimate with the plants at all stages. I think there must be great understanding between the painter and the thing painted otherwise there can be no conviction and no truth,’ he wrote.

Cedric Morris never saw flowers as floaty and ephemeral, but as intense and determined things, ‘symbols of strength and the eternity of existence. Flower painting was not merely just struggle and achievement but a crystallisation of past apprehensions’ he explained. He accorded emotions and behaviours to his plants: ‘I am afraid for my Japanese irises they are temperamental sluts.’ When he became a serious iris breeder after the Second World War, one friend remarked to the writer Ronald Blythe, that Cedric felt ‘his irises were raunchy blooms sticking their tongues out at the British establishment.’ Cedric Morris always saw himself an outsider - he was, as a gay upper-class man who did not follow the traditional path of army and country sports. Indeed, he was often in conflict with Suffolk gamekeepers for the overuse of pesticides.

In the 1920’s Cedric and his partner Lett Haines lived in Paris. Neither man had a formal British art school education. Paris had become a destination for artists from all over the world. A new system was springing up to serve their needs. Artists could rent a small space in a shared studio and with others painting next to and around them. Cedric and Lett could not help but absorb the work of the Cubists - Picasso, Juan Gris, Fernand Leger - and the Surrealists, Max Ernst and John Banting. He knew Christopher Wood in the 1920’s (he and Cedric went on painting trips together), and Ben and Winifred Nicholson in the 1930’s (she proposed him for the Seven and Five Society).

Towards the end of that decade, the couple moved to Dedham where Lett believed Cedric would concentrate on his painting, particularly of flowers, distilling much of what he had learned in Paris into a unique modernist style. Tony Gandarillas, the lover and sponsor of the young painter Christopher Wood, described twisting and sculptural flowers, often set against dark backgrounds, as having a spectral feel: ‘Cedric Morris’ painting style is animistic not humanistic. I mean one would not be surprised if some of his places grew in the night, as if by magic.’

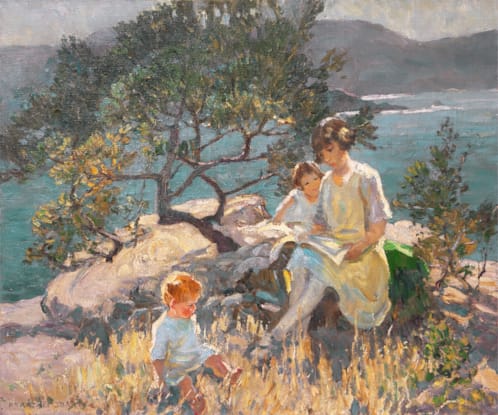

Surrealist Landscape, painted in the early 1950’s, which features another painting on the reverse side (Fig. 1), exhibits characteristics of his earlier works, encouraging viewers to observe human traits and hidden images within the flowers. Post-War, Cedric could resume annual trips to Europe, the Canary Islands and North Africa and his plant collecting in earnest. Rather than using a plain background, he positioned flowers in the foreground, not arranged in nature against the scenery in the background. This approach is also evident in the paintings of Winifred Nicholson. As the 1950’s progressed, the curtain of flowers with a panorama behind were replaced with flowers, often in vases and pots, less intense, less surreal and dramatic in colour contrast.

It is difficult to identify the location of the picture. The aim was to create an ambience and atmosphere rather than ensure accuracy. The plants he depicts in Surrealist Landscape are seasonably unaligned. The foliage in the top corner resembles a species of Sorbus, a Rowan tree (Fig. 2). The lily may be Lilium pyrenaicum (Fig. 3), from the Pyrenees taken to the Benton End Garden. The mauve iris, Benton Old Madrid, (Fig. 4) was cultivated by him, whereas the yellow iris, Iris variegata, (Fig. 5) was not developed by him. Pansies here are a rare inclusion.

The back of Surrealist Landscape (Fig. 1) is likely to have been painted in the 1930’s when Cedric spent a lot of time in Wales. Like Cubists, he drew inspiration from the countryside and its villages and towns. The abandoned cottage with a leaking roof and no windows is a comment on rural poverty. Individuals were relocating to seek employment in South Wales’ industries or to emigrate to the New World. Cedric, a dedicated Socialist, frequently helped the unemployed and poor impacted by the global financial depression. He accompanied Augustus John on tours of Wales and pleaded and petitioned councils and the Westminster government to help finance art studios and workshops to make things, to give work and raise morale.

Born in the Principality, his love of Wales was visceral. Being Welsh was very important to Cedric. He was keen to stress he was different from an Englishman:

‘I always said this was the loveliest in the world and it is so beautiful that I hardly dare look at it. I realise that all my painting is the result of pure nostalgia and nothing else. Everywhere is paintable, the colour is marvellous so is the shape my landscapes painted there are twenty times better.’

He asserted that Welsh art should be recognized independently rather than being categorised under British art. Cedric’s landscapes are influenced more by modern European styles than by traditional English ones. One art critic remarked that his work bore comparisons to Cézanne and Cubism. Cedric Morris, like Cézanne, favoured flattened perspective of the traditional linear giving a robust and immediate sensation.

It is likely that a combination of the war, and changing tastes in art after it, deemed his work unfashionable, so that he was unable to sell the picture of the Welsh cottage. He also had no strong ties to demanding galleries in London as he had done previously. The painting was taken to Benton End House near Surrealist Landscape presented ‘floating’ in a gilt, hollow frame Hadleigh, Suffolk, which became the new location of The East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing founded by Cedric and Lett. This followed a fire at the Dedham premises, allegedly set by a dropped lit cigarette of one the first pupils, Lucian Freud. Canvas was in short supply being needed for the war effort. Cedric decided to paint on the back of existing canvases and encouraged other students at the art school, such as Lucy Harwood, to do the same, sometimes on the back of his paintings.

The East Anglian Painting and Drawing School was flourishing and the garden too and ex-pupils such as Lucian Freud, Joan Warburton and Kathleen Hale visited often. Bettina Shaw-Lawrence was a contemporary student who maintained correspondence with Cedric and Lett. She was visiting Benton End one day in 1958 and Cedric decided to search through his stacked canvases with her. He retrieved the Surrealist Landscape and gave it to her. It had been in her family ever since.

Hugh St. Clair

Author of A Lesson in Art & Life: The Colourful World of Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines

Thence by descent within the family

‘In his flower painting Mr Cedric Morris has broken new ground. With his knowledgeable carelessness of production, he erects a screen of multi coloured petals. There is a frankness and simplicity about his treatment, as there is a natural instinct in his science, which has introduced an unwonted freedom into the conventions of this branch of paintings’, so wrote the esteemed art critic T.W. Earp in The Studio magazine in 1928. Cedric Morris remarked how he used to watch his mother work on her tapestries from top left to bottom right. His pictures have this element of structure within, and he often worked in that way.

Outlining his own thoughts about flower painting for The Studio in 1942, Cedric expressed admiration for Chinese flower painting, but also Van Gogh and the Surrealist Max Ernst. He never sought botanic accuracy preferring to convey realism and an inherent being within plants: ‘The artist must have been intimate with the plants at all stages. I think there must be great understanding between the painter and the thing painted otherwise there can be no conviction and no truth,’ he wrote.

Cedric Morris never saw flowers as floaty and ephemeral, but as intense and determined things, ‘symbols of strength and the eternity of existence. Flower painting was not merely just struggle and achievement but a crystallisation of past apprehensions’ he explained. He accorded emotions and behaviours to his plants: ‘I am afraid for my Japanese irises they are temperamental sluts.’ When he became a serious iris breeder after the Second World War, one friend remarked to the writer Ronald Blythe, that Cedric felt ‘his irises were raunchy blooms sticking their tongues out at the British establishment.’ Cedric Morris always saw himself an outsider - he was, as a gay upper-class man who did not follow the traditional path of army and country sports. Indeed, he was often in conflict with Suffolk gamekeepers for the overuse of pesticides.

In the 1920’s Cedric and his partner Lett Haines lived in Paris. Neither man had a formal British art school education. Paris had become a destination for artists from all over the world. A new system was springing up to serve their needs. Artists could rent a small space in a shared studio and with others painting next to and around them. Cedric and Lett could not help but absorb the work of the Cubists - Picasso, Juan Gris, Fernand Leger - and the Surrealists, Max Ernst and John Banting. He knew Christopher Wood in the 1920’s (he and Cedric went on painting trips together), and Ben and Winifred Nicholson in the 1930’s (she proposed him for the Seven and Five Society).

Towards the end of that decade, the couple moved to Dedham where Lett believed Cedric would concentrate on his painting, particularly of flowers, distilling much of what he had learned in Paris into a unique modernist style. Tony Gandarillas, the lover and sponsor of the young painter Christopher Wood, described twisting and sculptural flowers, often set against dark backgrounds, as having a spectral feel: ‘Cedric Morris’ painting style is animistic not humanistic. I mean one would not be surprised if some of his places grew in the night, as if by magic.’

Surrealist Landscape, painted in the early 1950’s, which features another painting on the reverse side (Fig. 1), exhibits characteristics of his earlier works, encouraging viewers to observe human traits and hidden images within the flowers. Post-War, Cedric could resume annual trips to Europe, the Canary Islands and North Africa and his plant collecting in earnest. Rather than using a plain background, he positioned flowers in the foreground, not arranged in nature against the scenery in the background. This approach is also evident in the paintings of Winifred Nicholson. As the 1950’s progressed, the curtain of flowers with a panorama behind were replaced with flowers, often in vases and pots, less intense, less surreal and dramatic in colour contrast.

It is difficult to identify the location of the picture. The aim was to create an ambience and atmosphere rather than ensure accuracy. The plants he depicts in Surrealist Landscape are seasonably unaligned. The foliage in the top corner resembles a species of Sorbus, a Rowan tree (Fig. 2). The lily may be Lilium pyrenaicum (Fig. 3), from the Pyrenees taken to the Benton End Garden. The mauve iris, Benton Old Madrid, (Fig. 4) was cultivated by him, whereas the yellow iris, Iris variegata, (Fig. 5) was not developed by him. Pansies here are a rare inclusion.

The back of Surrealist Landscape (Fig. 1) is likely to have been painted in the 1930’s when Cedric spent a lot of time in Wales. Like Cubists, he drew inspiration from the countryside and its villages and towns. The abandoned cottage with a leaking roof and no windows is a comment on rural poverty. Individuals were relocating to seek employment in South Wales’ industries or to emigrate to the New World. Cedric, a dedicated Socialist, frequently helped the unemployed and poor impacted by the global financial depression. He accompanied Augustus John on tours of Wales and pleaded and petitioned councils and the Westminster government to help finance art studios and workshops to make things, to give work and raise morale.

Born in the Principality, his love of Wales was visceral. Being Welsh was very important to Cedric. He was keen to stress he was different from an Englishman:

‘I always said this was the loveliest in the world and it is so beautiful that I hardly dare look at it. I realise that all my painting is the result of pure nostalgia and nothing else. Everywhere is paintable, the colour is marvellous so is the shape my landscapes painted there are twenty times better.’

He asserted that Welsh art should be recognized independently rather than being categorised under British art. Cedric’s landscapes are influenced more by modern European styles than by traditional English ones. One art critic remarked that his work bore comparisons to Cézanne and Cubism. Cedric Morris, like Cézanne, favoured flattened perspective of the traditional linear giving a robust and immediate sensation.

It is likely that a combination of the war, and changing tastes in art after it, deemed his work unfashionable, so that he was unable to sell the picture of the Welsh cottage. He also had no strong ties to demanding galleries in London as he had done previously. The painting was taken to Benton End House near Surrealist Landscape presented ‘floating’ in a gilt, hollow frame Hadleigh, Suffolk, which became the new location of The East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing founded by Cedric and Lett. This followed a fire at the Dedham premises, allegedly set by a dropped lit cigarette of one the first pupils, Lucian Freud. Canvas was in short supply being needed for the war effort. Cedric decided to paint on the back of existing canvases and encouraged other students at the art school, such as Lucy Harwood, to do the same, sometimes on the back of his paintings.

The East Anglian Painting and Drawing School was flourishing and the garden too and ex-pupils such as Lucian Freud, Joan Warburton and Kathleen Hale visited often. Bettina Shaw-Lawrence was a contemporary student who maintained correspondence with Cedric and Lett. She was visiting Benton End one day in 1958 and Cedric decided to search through his stacked canvases with her. He retrieved the Surrealist Landscape and gave it to her. It had been in her family ever since.

Hugh St. Clair

Author of A Lesson in Art & Life: The Colourful World of Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines

Biography

Cedric Morris was born 11th December 1889, the eldest son of Sir George Lockwood Morris, 8th Baronet, at Sketty in Glamorganshire, South Wales. He was educated at Charterhouse following which he farmed in Canada and then Wales.

In 1913 he decided to pursue a career as a painter, studying in Paris. On the outbreak of war he served in the army, 1914-15 in the ranks and then in the Remounts working with horses under the artist Cecil Aldin (1870-1935).

In 1918 he returned to art joining his partner Arthur Lett-Haines (1894-1978) a fellow artist, in Chelsea. Morris returned briefly to Newlyn in Cornwall where he had spent 1918 sketching before he and Lett-Haines based themselves in Paris 1921-27. Here they mixed with the expatriate artistic community while also travelling extensively through France, Spain and Italy. In 1922, Morris and Lett-Haines held solo exhibitions in Rome.

Returning to London in the late 1920’s Morris joined the London Group and was proposed by Ben Nicholson (1894-1982) for membership of the Seven and Five Society.

However, though retaining a studio in London, Morris and Lett-Haines moved to Colchester when he worked at Pound Farm founding the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing in 1935, based in Higham and from 1940 at his home in Benton End, Hadleigh, Suffolk.

The EASPD at Benton End was a liberal and unconventional art school in which discussion and the surrounding gardens played as significant a part as teaching. A renowned plantsman and gardener, Morris was as unconventional as he was as a teacher, his planting veered towards the natural rather than the uniform ordered style, then in vogue. Numerous students left Benton End with this philosophy in both painting and gardening, and a love of the Mediterranean cuisine at which Lett-Haines, a friend of Elizabeth David, was so accomplished.

Among the many students who studied with Morris in London and East Anglia was Lucian Freud (1922-2011), a portrait of whom dating from 1941 by Cedric Morris is in the Tate. Morris was President of the South Wales Art Society and was on several occasions invited to become an Associate of the Royal Academy, which he refused. He was a founder member of the Colchester Art Society along with his friend and fellow plantsman, John Nash (1893-1977)

As a plantsman, Morris was widely respected as a breeder of irises; he was a countryman with an extraordinary affinity with nature, who decried intensive farming and the overuse of pesticides, beliefs reflected in a number of his paintings.

A painter in oils and watercolours of landscape, still life, flower studies and portraiture, Morris was a leading and influential 20th century painter. He rejected abstraction and retained a style of his own throughout his career. He was a keen and knowledgeable horticulturalist, a passion evident in his flower paintings.

Morris, having inherited the Baronetcy in 1947, died in 1982.

His works can be found in museums in: Belfast, Ulster Museum; Cardiff, The National Museum of Wales; London, Tate Britain; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Melbourne, The National Gallery of Art and public collections in Aberdeen, Aberystwyth, Bradford, Chichester, Colchester, Eastbourne, Hull, Manchester, Norwich, Oldham, Southampton and Swansea.

In 1913 he decided to pursue a career as a painter, studying in Paris. On the outbreak of war he served in the army, 1914-15 in the ranks and then in the Remounts working with horses under the artist Cecil Aldin (1870-1935).

In 1918 he returned to art joining his partner Arthur Lett-Haines (1894-1978) a fellow artist, in Chelsea. Morris returned briefly to Newlyn in Cornwall where he had spent 1918 sketching before he and Lett-Haines based themselves in Paris 1921-27. Here they mixed with the expatriate artistic community while also travelling extensively through France, Spain and Italy. In 1922, Morris and Lett-Haines held solo exhibitions in Rome.

Returning to London in the late 1920’s Morris joined the London Group and was proposed by Ben Nicholson (1894-1982) for membership of the Seven and Five Society.

However, though retaining a studio in London, Morris and Lett-Haines moved to Colchester when he worked at Pound Farm founding the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing in 1935, based in Higham and from 1940 at his home in Benton End, Hadleigh, Suffolk.

The EASPD at Benton End was a liberal and unconventional art school in which discussion and the surrounding gardens played as significant a part as teaching. A renowned plantsman and gardener, Morris was as unconventional as he was as a teacher, his planting veered towards the natural rather than the uniform ordered style, then in vogue. Numerous students left Benton End with this philosophy in both painting and gardening, and a love of the Mediterranean cuisine at which Lett-Haines, a friend of Elizabeth David, was so accomplished.

Among the many students who studied with Morris in London and East Anglia was Lucian Freud (1922-2011), a portrait of whom dating from 1941 by Cedric Morris is in the Tate. Morris was President of the South Wales Art Society and was on several occasions invited to become an Associate of the Royal Academy, which he refused. He was a founder member of the Colchester Art Society along with his friend and fellow plantsman, John Nash (1893-1977)

As a plantsman, Morris was widely respected as a breeder of irises; he was a countryman with an extraordinary affinity with nature, who decried intensive farming and the overuse of pesticides, beliefs reflected in a number of his paintings.

A painter in oils and watercolours of landscape, still life, flower studies and portraiture, Morris was a leading and influential 20th century painter. He rejected abstraction and retained a style of his own throughout his career. He was a keen and knowledgeable horticulturalist, a passion evident in his flower paintings.

Morris, having inherited the Baronetcy in 1947, died in 1982.

His works can be found in museums in: Belfast, Ulster Museum; Cardiff, The National Museum of Wales; London, Tate Britain; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Melbourne, The National Gallery of Art and public collections in Aberdeen, Aberystwyth, Bradford, Chichester, Colchester, Eastbourne, Hull, Manchester, Norwich, Oldham, Southampton and Swansea.